When practicing aromatherapy, every Registered Aromatherapist (RA) should be working with the best oils to achieve the desired therapeutic effects. Learning to assess the quality of an essential oil is much like developing a "nose" with which to enjoy fine a wine and distinguish the complexities in the flavor. The aromatherapist’s "nose" is one of the tools used to identify extenders, diluents, and synthetics, all of which can be used to adulterate essential oils.

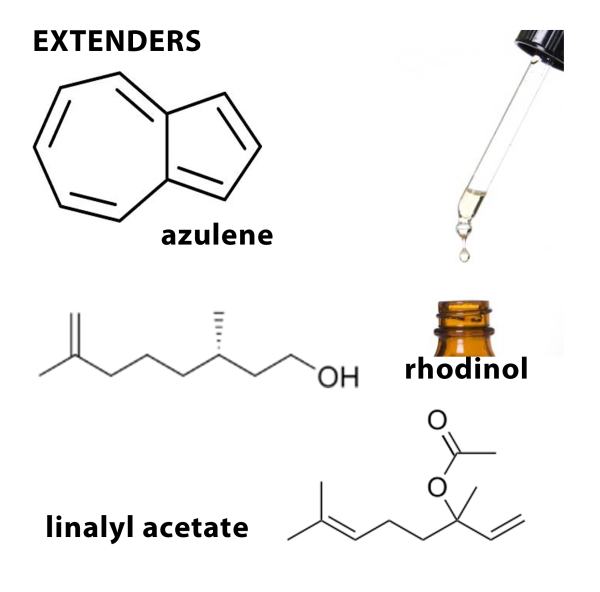

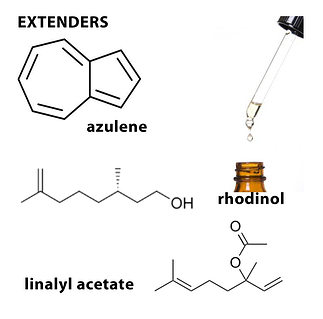

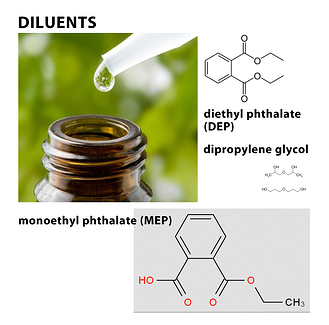

There are a few ways that essential oils can be compromised. Diluents are substances that are usually odorless and are added to the products for commercial reasons. Extenders are inexpensive aroma materials that may or may not have an identical fragrance and are usually synthetic.

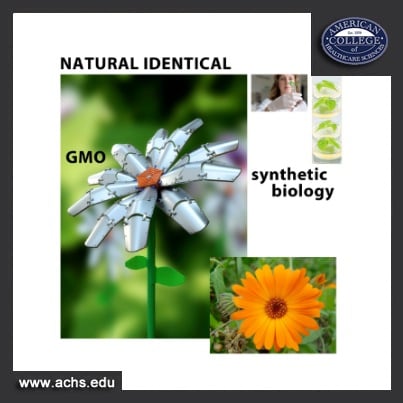

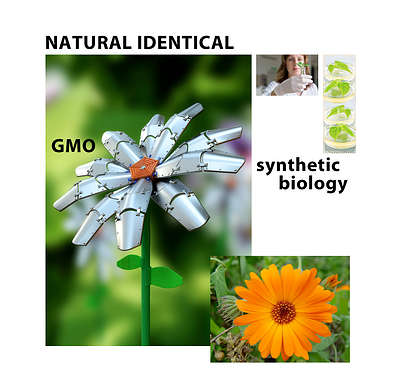

One phrase to look out for is: “nature identical.” This should be a red flag, and usually refers to a chemically synthesized version of the oil. Nature identical, diluted, or extended oils are not suitable for clinical therapeutic aromatherapy. Nature identical oils—or the use of single synthetic constituents—do not account for the synergistic actions of whole plant oil.

Did you know that genetically modified (GMO) sourcing doesn't only apply to food? Nature identical would also apply to GMO sourced fragrance and flavor materials created using synthetic biology—something we are seeing more of in the world of fragrance and flavor.

Another important term and concept every aromatherapist should know is "synergy." Synergy is based on the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, and it exists within each individual oil and within blends of specific oils.

A useful example of how synergy works can be seen in a study conducted in 1974. The study focused on Eucalyptus citriodora (Hook.), which showed more effective antimicrobial activity in the whole oil than in the separate components, citronellal and citronellol (Low et al., 1974). Another sutdy in 1993 focused on the antifungal activity of limonene. Sweet orange Citrus sinensis (Osbeck) was found to have strong antifungal activity against fungi, such as Aspergillus niger. Limonene was separated from the oil and found to be the antifungal constituent, but it was less active than the whole oil. It was concluded that the presence of other constituents, even in low proportions, created a synergistic effect, enhancing the overall antifungal activity (Singh et al., 1993).

Synergy is also a factor when arometherapists blend essential oils for clinical therapeutic formulae. For clinical work, oils with similar constituents can enhance activity. Research has shown greater antimicrobial activity when oils are combined. One study showed this to be the case even when some of the oils showed no activity on their own (Geda, 1995). Tea tree Australia Melaleuca alternifolia (Cheel) is one exception to the synergy theory. The constituent terpinen-4-ol has been found to be more active in some circumstances when administered as a single constituent than when used as a complete tea tree oil (Cox et al., 2001).

Synergy can even occur between pharmaceuticals and essential oils. A 2011 study performed in Iran showed a synergistic effect between the antibiotic ciproflaxin and geranium Pelargonium graveolens (L'Her.) essential oil against bacteria that commonly cause urinary tract infections, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Staphylococcus aureus (Malik et al., 2011). The intangible quality of synergy cannot be replicated in a laboratory

In addition to the benefits of synergy, a supplier may be unaware that a diluted or extended oil can pose problems for the clinical aromatherapist where oils may be used on the skin or administered internally.

Diluents such as diethyl phthalate (DEP), for instance, can cause toxic reactions when administered orally or topically. DEP is made from ethanol and phthalic acid and is a permitted substance in fragrance products where skin contact is minimal; however, an essential oil is not safe to use when DEP is present for the administration of clinical aromatherapy. Aromatherapists are trained to conduct organoleptic testing that exposes this diluent by identifying its bitter and unpleasant taste, which is also irritating to mucous membranes. When this material is absorbed through the skin, it depresses the nervous system, and current research indicates possible cancer-causing effects as well. A 2010 study examined whether or not there is a relationship between urinary levels of nine different phthalates and the incidence of breast cancer. In this study, urinary phthalate metabolites were detected in 82% of the women, whether or not they had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Monoethyl phthalate (MEP), a urinary metabolite of the parent compound DEP, was elevated in women with breast cancer. Aromatherapists are taught that DEP is most often found in sandalwood Santalum album (L.), and benzoin Styrax paralleloneurum (Perk.) oils but may also be found in other oils. One simple test for DEP that is recommended is to put a single drop of the oil on the tip of the tongue. If the oil contains DEP, the tongue will feel numb. However, aromatherapists trained to recognize that the eugenol content of oils, such as rose Rosa damascena (Mill.) oil, can also make the tongue numb and does not mean the oil is adulterated in this case.

Diluents such as diethyl phthalate (DEP), for instance, can cause toxic reactions when administered orally or topically. DEP is made from ethanol and phthalic acid and is a permitted substance in fragrance products where skin contact is minimal; however, an essential oil is not safe to use when DEP is present for the administration of clinical aromatherapy. Aromatherapists are trained to conduct organoleptic testing that exposes this diluent by identifying its bitter and unpleasant taste, which is also irritating to mucous membranes. When this material is absorbed through the skin, it depresses the nervous system, and current research indicates possible cancer-causing effects as well. A 2010 study examined whether or not there is a relationship between urinary levels of nine different phthalates and the incidence of breast cancer. In this study, urinary phthalate metabolites were detected in 82% of the women, whether or not they had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Monoethyl phthalate (MEP), a urinary metabolite of the parent compound DEP, was elevated in women with breast cancer. Aromatherapists are taught that DEP is most often found in sandalwood Santalum album (L.), and benzoin Styrax paralleloneurum (Perk.) oils but may also be found in other oils. One simple test for DEP that is recommended is to put a single drop of the oil on the tip of the tongue. If the oil contains DEP, the tongue will feel numb. However, aromatherapists trained to recognize that the eugenol content of oils, such as rose Rosa damascena (Mill.) oil, can also make the tongue numb and does not mean the oil is adulterated in this case.

Another diluent that aromatherapists are trained to identify is dipropylene glycol, a clear colorless liquid that gives essential oils a sweet taste. It is absorbed through the skin better than glycerin but is linked to more sensitivity reactions (Winter, 2009). It is often found in expensive oils, such as sandalwood, and is usually not indicated on the label.

Extenders are even more problematic. Although they mimic the natural chemical compound found in essential oils, they produce effects that the natural oil would not produce and consequently they are metabolized quite differently. They do not behave in the body as expected.

Examples of unacceptable adulteration practices for clinical aromatherapy include lavender Latin names. Lavandula angustifolia (Mill.) adulterated with synthetic or naturally sourced linalyl acetate, linalol, and other synthetically duplicated substances; chamomile Chamaemelum nobile (L.) oil enhanced by adding synthetic azulene; and rose otto R. damascena adulterated with rhodinol.

Adding a fixed or fatty oil to an essential oil is also unacceptable for a clinical aromatherapist.

Aromatherapists are trained to test for this by rubbing a small sample of the essential oil between the thumb and middle finger or dropping the oil on a perfume-testing blotter. An extended oil will feel slick or even slimy, leave a greasy spot on the testing strip, and will not evaporate completely.

Rancidity is another factor that aromatherapists are alerted to. While most essential oils will alter over a long period, they do not produce the rancid odors of a vegetable or fixed oil. Other liquids, such as alcohol, are also not suitable for clinical aromatherapy when used to adulterate oils.

In addition, ACHS clinical aromatherapist graduates are trained to inspect the oil for signs of impurity when in a crystallized state. Oils such as anise Pimpinella anisum (L.) and rose R. damascena reveal a lot with this simple test. Both oils solidify and crystallize in cool temperatures. When crystallized, adulterated oils will reveal the adulterating substance, which either rests on the bottom or floats on top. This is a great test as solidified or crystallized oils kept at room temperature for a few hours will liquefy with no destructive effects to the oil.

As you can see, there are a number of ways aromatherapists and consumers can evaluate the quality of an essential oil. ACHS recommends formal training in aromatherapy or working with Registered Aromatherapist (RA) before using essential oils for therapeutic use. Both for safety and to maximize results, be sure you have appropriate training to use essential oils.

Check back next week for my next blog article on assessing the quality of essential oils: I Say Lavender, You Say Lavandin...Is it the same thing?